Not all stouts are created equal. In just the last year, we’ve written about how to brew the best milk stouts, oatmeal stouts, pastry stouts, imperial stouts, and even chocolate stouts. But sometimes, a simple beer, like a dry Irish stout, can become one of the most popular beers in the world.

Guinness is the standard for many breweries in how they concoct their dry Irish stouts. And for good reason. For the last six years, Guinness Draught has topped the Untappd charts as the beer with the most global check-ins.

For this piece, we chatted with two other well-known American dry Irish stout makers, Trillium and Roaring Table, to learn more about the top things to consider when brewing this style and how to execute a quality beer—even if it’s not a clone of Guinness.

(Above Photography courtesy of Guinness)

What We’ll Cover in This Piece:

Affordable, Industry-Leading Brewery Software

How Do the Experts Define Dry Irish Stout?

Roaring Table Co-Owner Lane Fearing says that Guinness is the iconic stout for him and is the dry Irish stout he has in mind when considering the style’s definition.

“It’s my North Star when it comes to Irish stout,” Fearing says. “A properly poured stout is creamy, the mouthfeel and the way it approaches your palate is soft and pleasant, and the backing of the roastiness balances out the softness.”

Fearing also says that the stout is a “pub-friendly beer” low in CO2 and easy to drink.

“It seems like the perfect pint in the English or Irish tradition of a session at a pub,” Fearing says.

Trillium Co-Founder Jean-Claude Tetreault points to the BJCP guidelines when talking about the definition of dry Irish stout.

“The guardrails of the BJCP are narrow,” Tetreault says. “It’s a comforting beer you can relax with. It’s pretty homey.”

Tetreault says the best example of the style is Guinness.

“Landmarks of the style are drinkability, quenching drying roast with a firm bitterness,” he says. “There is a slight brightness to it from the acidic nature of the grain. The lower ABV and low finishing gravity add to the quenching nature of the beer.”

What Are the Top Considerations for Brewing Dry Irish Stout?

Tetreault says it’s all about intention.

“We look at a classic recipe and classic ingredients, and we try to put that in the context of what we think a new customer might want and expect,” Tetreault says.

Tetreault says that beer nerds will say that what they are making is not an Irish stout—based on their grain selection, finishing gravity, SRM, and IBUs, it’s the closest frame of reference. But he says only one thing is crucial, no matter the stout.

“We want to brew and package this well in advance,” Tetreault says. “Some of these depths [of flavor] don’t come through for at least a month.”

Once complete, Tetreault says having the beer on nitro is a good twist.

“The beer is packed with character, and it doesn’t lose much on nitro,” Tetreault says. “[Nitro] does magic for this beer.”

Fearing admits to evolving his thinking of how to make dry Irish stouts and focuses on the mash pH.

“Making sure it isn’t too low,” Fearing says. “It seems like a higher mash pH range—around 5.5—lends a softer roast.”

Another thing to consider is mashing your base grains and then mash-capping darker malts.

“Adding chocolate and roasted malts after the mash is over and going right into the vorlauf doesn’t give [the roasted malts] enough time to get that acrid taste,” Fearing says. “Doing that keeps us from making the beer astringent.”

In early iterations of their dry Irish stout, Fearing says they let the pH get too low, and it was too “light and zappy.” Over time, he says they’ve perfected the beer through these steps.

“There’s roast, but the creaminess is very evident,” Fearing says. “It’s a simple beer. There’s not much to it. But what we’ve been doing has been working for us.”

What Are the Challenges of Making Dry Irish Stout?

Fearing says water chemistry can be a challenge with the beer.

“We’ve used baking soda because we mashed in all the grains at once,” Fearing says. “If you separate the two, you can do a simple chemistry on the main mash. I like low ionic water with these.”

He reiterates that by mash-capping, Roaring Table could keep a simple water profile.

“When the pH drops with mash-capping, it’s okay because it’s heading into the kettle,” Fearing says. “It’s a better overall beer from it.”

Tetreault agrees with the importance of water chemistry in dry Irish stouts.

“Make sure you have sufficient alkalinity/bicarbonate,” Tetreault says. “You need enough buffering capacity to account for the acidifying impact of the roasted grain for it to land at the target.”

Tetreault adds, “Sufficient minerals are always needed for yeast health, but excessive levels or permanent hardness lends an unpleasant chalky texture.”

He also notes that hitting your finishing gravity needs to be intentional.

“If you want it on the drier stouts, you gotta hit your finishing gravity,” he says.

And patience is imperative, which presents a challenge if you don’t leave ample time before a planned release.

“Fresh [dry Irish stouts] are enjoyable but feel awkward in their adolescence,” he says.

What Is a Great Grist Bill for Dry Irish Stout?

Tetreault admits they take their dry Irish stout in a different direction than what the guidelines would advise.

“We look to add breadth and depth to the malt character from our take of an Irish stout,” Tetreault says. “Where you might look at one or two specialty grains, we look at it from what we learned from our bigger stouts and add eight specialty grains.”

He says they use 64.5 percent Munich malt, 11 percent two-row, 3 percent flaked barley, 5 percent each of chocolate malt and crystal medium malt, 4 percent of DRC, and 1.5 percent of each brown malt [British], Caramalt [British], Crystal Light [British], roasted barley [British], and chocolate wheat.

Fearing explains the Roaring Table grist uses 60 percent Maris Otter, 23 percent flaked barley, and 15 percent roasted malts, namely roasted barley and pale chocolate.

“I feel like adding pale chocolate adds an extra dimension,” Fearing says.

What IBUs Are Best for Dry Irish Stout?

“We don’t feel hops are a big player in this,” Fearing says, noting Roaring Table uses Magnum hops in the recipe “We target thirty-three BUs and let the roast do most of the talking with these.”

Tetreault likes to put a little more emphasis on the hops for his dry Irish stout.

“I want to achieve forty BUs,” he says. “You can use some combo of a clean high alpha acid hop and then East Kent Goldings [EKGs] to add continental character.”

He adds, “There is some texture, body gained. Using both is a good approach. Even like a Magnum in combo with EKGs and getting 50 percent of BUs from each is a good approach.”

What ABV Makes for an Ideal Dry Irish Stout?

Dry Irish stout is a lower-ABV beer. Guinness Draught hits at 4.2% ABV. Tetreault takes his a little higher but reiterates that Trillium’s version isn’t the true-to-guideline style.

“We’re at 5% ABV for ours,” he says. “BJCP says it should be anywhere from 4% ABV to 4.5% ABV.”

Fearing is more closely aligned with the guidelines, with their dry Irish stout at 4.1% ABV.

“That’s what I like,” he says. “The great thing about drinking these is you can have a nice session, and you don’t get drunk or get too sleepy or full … 4% ABV to 4.5% ABV is perfect.”

Two Great Examples of Dry Irish Stout

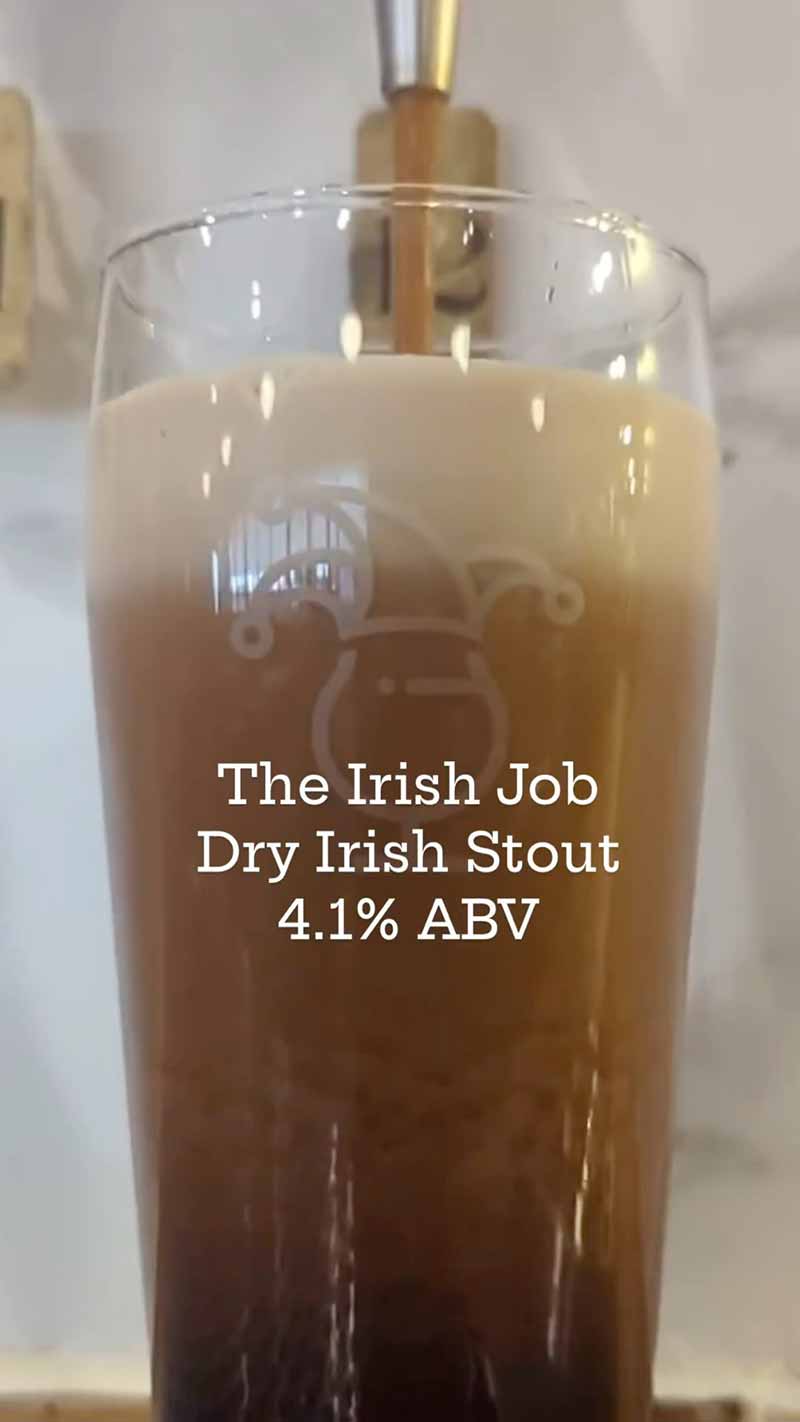

Roaring Table has The Irish Job. The 4.1% ABV stout is gaining popularity with the brewery’s customer base.

“Our aim was to create a roasty, slightly chocolatey, light-body, light-ABV beer,” Fearing says. “It’s so flavorful, it’s light, and disappears [from the glass quickly].”

Fearing only serves The Irish Job in the taproom on nitro, saying having the beer on tap is an educational opportunity.

“What’s so fun is people recognizing how approachable and sessionable a dry Irish stout is,” Fearing says. “A lot of people have these skewed interpretations of what stouts are. To experience this stout helps broaden our customers’ horizons.”

Trillium makes its Irish Stout each year around St. Patrick’s Day. Knowing the plethora of Irish stout releases around that time, Tetreault says that’s why Trillium takes a different approach. At 5.2% ABV, their take includes eight specialty grains and a deep malt character.

“We took a risk with a relatively significant departure from this,” Tetreault says. “We aren’t looking to open the BJCP stylebook and copying that. We like to explore different grists and such. The moment for what the beer is intended for is what we were trying to achieve in this recipe.”