Whether you get your buzz in the morning (with coffee) or your buzz at night (with beer), there’s no denying that one of craft brewers’ brilliant moves has been putting the two together.

Putting coffee into beer can probably be traced back to the mid-to late-1990s when Dogfish Head Brewery, Wisconsin’s New Glarus Brewing, and AleSmith Brewing Company all released coffee stouts.

A style perfect for an addition of java, stouts, with their darker malts, provided a deep dark base that perfectly complemented the roasted qualities of coffee beans. In other words, a beer style chockful of chocolate character highlighted those same flavor profiles in coffee.

In the next couple of decades, many iconic versions of coffee beers emerged, including Founders Brewing Breakfast Stout, Three Floyds Dark Lord, and Toppling Goliath’s Mornin’ Delight, to name a few.

Today, with over 9.1k breweries in the country (Brewers Association,) it’s actually probably pretty hard to find a brewery that hasn’t experimented with putting beans, grinds, cold brew, espresso, and more into a recipe.

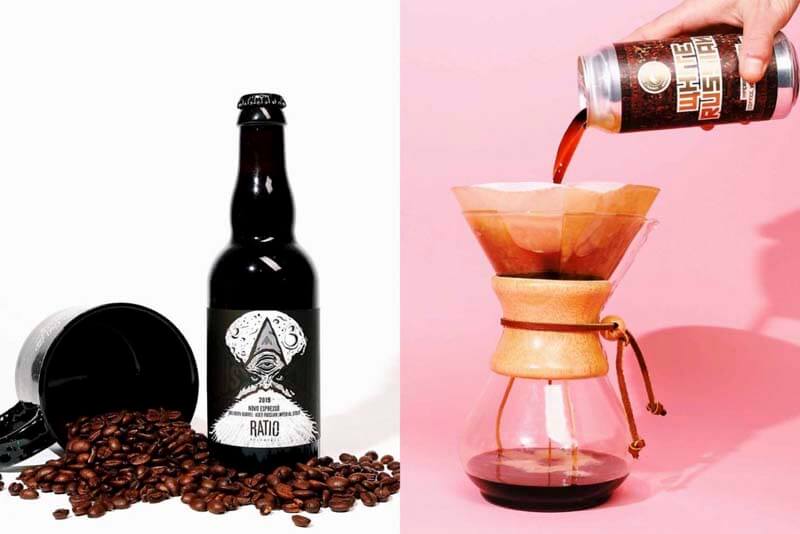

Above photo: Photography courtesy of @alesmithbrewing (on the left) and Wooden Robot Brewery (on the right)

And the experimentation with coffee has expanded way beyond stouts and porters, encompassing all manner of styles from coffee blonde ales to coffee lagers to coffee cream ales to coffee saisons to even coffee IPAs.

At this point, the permutations for writing a coffee beer recipe probably number in the hundreds of thousands.

In an article for Hop Culture on Everything You Need to Know About Coffee Beers, Moksa Brewing Company Head Brewer Derek Gallanosa says there are “hundreds of combinations that a brewery can use” for making coffee beer.

So here, we’ve done our best to wrangle this ever-popular style, breaking down all the different choices you can make to show you the pros and cons of all the considerations you need to make in order to brew your best coffee beer. (Hint: it included drinking many cups of coffee and pints of coffee beer)

What We’ll Cover in This Piece:

Affordable, Industry-Leading Brewery Software

What Makes a Good Coffee Beer?

Photography courtesy of @alesmithbrewing | AleSmith Brewing Company

Before you even attempt to brew a coffee beer, it’s important to understand the building blocks to a great one. Otherwise, what’s the point of even attempting to add coffee into a recipe?

“The most important thing is balance,” says Wooden Robot Brewery Co-Founder and Head Brewer Dan Wade. “You want the character of the coffee to complement the character of the beer, not overpower it or get lost in it.” At Wooden Robot, Wade has experimented with a wide variety of coffee beer styles, but at the moment his coffee vanilla blonde ale called Good Morning Vietnam is the most popular. In fact, the North Carolina-based brewery loves brewing with coffee so much that they even installed their own coffee bar in the taproom six months ago.

All in the pursuit to continue finding not only the best way, but also more innovative ways to add coffee to beer. But despite the experimentation, Wade says that he always comes back to that key word: balance.

The same can be said by AleSmith Brewing Company Head Brewer Anthony Chan. “A good coffee beer should let the coffee shine,” says Chan. “What’s really important is that you maintain the beer itself, that it has a good balance between coffee and beer, not one or the other.”

He continues hammering this point home. “You should know you’re drinking a coffee beer,” he says. “What’s really important is that the aroma and flavor carries through all the way.”

But what are the best ways to achieve this balance?

It will all come down to the decisions you make around a few key variables: “The amount of coffee you want to use, the variety and roast of coffee you want to use, how you are going to crush it, then how much time and temperature you’re going to expose it to,” says Wade.

Preparation will be crucial and it all starts with figuring out where to source your coffee.

What Are the Best Ways to Source Coffee?

Photography courtesy of Wooden Robot Brewery

The options are truly endless here, but in talking with both Wade and Chan, along with AleSmith Brewing Company Quality Manager Peter Cronin, we have a few tips to share.

Source Locally

At Wooden Robot, Wade works with a local roaster called Enderly Coffee Company. He says the benefits of working with someone close by are numerous.

“Obviously freshness is important, so having a local supplier helps a ton,” says Wade.

Plus, it’s easier to develop a relationship with someone in your neighborhood. Some place you or your fans may frequent daily.

Reach out to a local roaster you like and see if they’d be interested in working together.

Source Globally

For Southern California-based AleSmith, they’ve gone both routes. But sourcing globally can be helpful when it comes to the different variants of Speedway Stout. For instance, when making Hawaiian Speedway Stout, AleSmith sources coffee from Hawaii. And, when making Mexican Speedway Stout, the brewery will source from Mexico. For regular Speedway Stout, a blend of three different coffees come from Central America and Brazil.

Finding a Roaster

However you actually decide to source, there is something to be said for starting local. At the very least, your neighborhood coffee company can be a reputable source for giving you ideas about good farms to work with if you do want to go global.

“We have some sources that roast and source beans locally…they’ll give us a selection of farms they know,” says Chan.

Either way, having a good relationship with your roaster is extremely important.

Mostly because your roaster can help you pick out the varietal and roast that will work best for your recipes.

For example, the first time AleSmith brewed Hawaiian Speedway they reached out to a local Hawaiian coffee roaster called Swell. “They were like, oh man, you have to try this Ka’u coffee,” recounted Cronin. “[They told us] everyone knows Hawaii for Kona, but that’s not what the locals are drinking; they’re drinking Ka’u. We tried it, we did a cupping, and it was amazing.”

Just like you know beer best, you can bet that coffee roasters know coffee best.

“They know their products better than anyone else,” says Wade. “We have the roaster pick out some beans they’re already roasting to their spec they would want to make a good cup of coffee with and do a blind tasting to really find what works best for each flavor profile for a beer we’re working on.”

Use your roaster’s knowledge to your advantage, leverage their expertise to find the best bean variety and roast level for your beer.

What Type of Roast Works Best With a Coffee Beer?

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso | Hop Culture

Well, that all depends on the base style you’re trying to make. But a good rule of thumb should be that you match the color of your base beer with the color of the roast.

Darker styles like stouts and porters tend to work well with medium roasts while lighter styles like blonde ales and IPAs go better with lighter roasts.

“For the most part, we start with medium to medium-dark roast because medium is usually the way to go to get that roast flavor,” says Chan referring to darker styles of beer. “[But] with a base beer like pale ale that’s lighter go with a lighter roast.”

For example, Good Morning Vietnam, the coffee blonde ale from Wooden Robot, uses what Wade calls a blonde roast coffee because it just made sense. “We used these lighter, brighter characters of coffee with this lighter beer style and built a base beer to highlight that.”

Either way, it’s probably best to stay away from completely dark roasts because they can overpower the balance in the beer.

“With dark roast coffees you’re roasting out a lot of the more nuanced, interesting varietal character of coffee,” says Wade. “Once you get past medium roast you just start tasting dark roast coffee.”

For that reason, at Wooden Robot, Wade says that he sticks with lighter-to-medium roasts in his beers. “A great chef or great brewer is doing the best to do as little as possible to mess with great characteristics of the ingredients they’re working with,” says Wade. “Because of that, those blonde-to-medium roast coffees bring out the character you really want that the bean has to begin with.”

A Word on Natural vs. Washed Coffee

Chan says it’s also important to understand the different processing methods for the coffee you’re trying to use. Processing coffee breaks down into two approaches: washed or natural varieties.

Washed coffee involves removing the cherry around the seed and putting it into water where it undergoes fermentation to remove any additional flesh. Post-fermentation the coffee is dried. This method really preserves the essence of the coffee bean. Most coffees you’ll find today use beans that have been washed.

Natural, on the other hand, is one of the oldest ways to process coffee after it’s harvested. Essentially, the coffee cherry is dried and then, along with the husk, taken off the seeds. This method means a longer contact time for the coffee seed with the fruit and sugars. Oftentimes, it results in fruitier flavors from the bean in the long run.

“Natural are cool because they are based on the fruit, so you get more fruity, more delicate [flavors],” says Chan. “They don’t make their way through in imperial stouts, but they come through nicely in a lightly hopped ale.”

Just another consideration to make based on the style of beer you’re trying to brew.

Should You Use a Single Varietal or Blends?

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso | Hop Culture

Like with any decision you need to make when designing and brewing a coffee beer, there are pros and cons to both options.

Single Varietal Coffee Beans

Much like making a lager, there is less to hide behind with a single varietal. “You want that to shine in balance with everything else,” says Cronin. “You’re paying for a single varietal, so you better get it in the final product.”

Not to say that single varietals can be more expensive per se, just that you’re investing in only one type of bean, so you want to make sure that your balance is spot on.

The best way to think of it is in terms of hops. If you’re making a SMaSH (single malt and single hop) or even just a single hop beer, you want that hop to be the star, right? The same rule applies when using single varietals.

For that very reason, using just one coffee variety can be tricky.

“Single varietals need to match the “impact factor,”” says Cronin, referring to a sensory term for a beer. “Speedway is a really high impact beer, so if something can’t put up a fight against it, it will flounder. You need a coffee that’s willing to fight, a contender.”

Which is why for beers like Speedway using a single varietal can be challenging. Cronin recommends reaching out to your roaster, telling them what you’re looking for and what the base beer is all about, and letting them give a recommendation.

Coffee Bean Blends

Blends, on the other hand, can be a little more forgiving. Cronin cites using blends as kind of an old trick at AleSmith. Way back, almost twenty-nine years ago, in the early days of the brewery, aromatic hops were hard to come by. And even those ones the brewery could get its hands on might have questionable quality. The workaround was to throw a ton of different hops into the kettle. “Let’s use little bits of each one and if one falls out the other will pick it up,” says Cronin, noting that those early AleSmith IPA recipes had up to thirteen hops in them.

Similarly, by using a blend of coffee beans, you can sort of even the playing field and create something that balances notes out across the board. “Our blended coffee works well because we get chocolate notes from a Central American coffee while we get darker notes from a Brazilian coffee,” says Cronin.

How Fresh Should Your Roasted Coffee Be?

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso | Hop Culture

Now that you’ve found a roaster, picked out a bean, and decided on the roast level, the next question is: How quickly should you use the bean after it’s been roasted?

“A lot of coffee experts tell you to wait a couple days for that bean to off gas after roasting,” says Wade. “Usually, we’re grinding and adding coffee two-to-three days after being roasted.”

Here’s what happens: After roasting, coffee beans let off gasses like carbon dioxide and sulfur, flavors that you certainly don’t want in your beer, but that will end up in the finished product if you don’t give your beans time to de-gas. This is why you often see beans in bags with a one-way breathable valve, which lets carbon dioxide out without letting oxygen in.

“When you have a coffee beer and there is a sulfur note you can definitely tell,” says Cronin. “Maybe they added it freshly roasted.”

To avoid this, both Cronin and Chan recommend brewing an actual cup of coffee with the beans just to taste it. If you’re getting some sulfurous flavors from the freshly brewed cup of coffee, wait a little bit longer before adding it to your recipe.

“When we buy coffee we’ll always save five pounds to brew coffee to try so we know what we’re getting,” says Chan. “There is no real hard, fast rule for how long we rest, but generally two-to-three days.”

However, at the same time, ground coffee starts to turn around day three or four (tricky, we know!). Using beans past their prime can allow them to oxidize, introducing what’s been described as a green-bell-pepper-like flavor into your final beer or what AleSmith calls “farting.”

“Wait too long, it will just smell like fart or green pepper,” says Chan.

Both Wooden Robot and AleSmith have found that letting your grounds rest two-to-three days before adding them into the beer work best.

“The big thing is making sure that we’re grinding it fresh in house so that we’re getting max freshness and giving the coffee an appropriate amount of time to sit after roasting, “ says Wade.

The Word on Whole Beans vs Cracked Beans vs Ground Coffee

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso | Hop Culture

To this point, we’ve been speaking exclusively about ground coffee. However, whole beans are another way to introduce coffee into beer.

But be careful here.

According to Chan, whole beans have a very low extract rate, meaning they don’t impart as much coffee flavor or aroma as ground beans.

Wade agrees. “There is a reason that when people make coffee they grind the beans,” he says. “All of the oils that have all the character are on the inside. What’s on the outside has been the most heavily roasted part, so you’re only getting a portion of the whole flavor profile of the coffee if you’re not grinding it.”

If you want to use whole beans consider using them to add flavor to a barrel-aged beer. For example, you could age a stout in a barrel with coffee beans.

But if you’re looking for a higher extraction rate of coffee flavor and aroma when you add your coffee beans in during fermentation, ground coffee or even cracked beans work best.

A method AleSmith kind of macgyvered, cracking beans involves putting them into a bag and basically smacking them with a hammer to just lightly crack them.

AleSmith found that adding cracked beans to a brite tank is kind of the best of both worlds.

“Cracked beans won’t over extract very quickly like ground coffee but you get more extraction than a whole bean,” says Cronin.

What Type of Grind Gives You the Best Extraction Rates?

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso | Hop Culture

Just one more variable in the coffee-beer-decision tree: The type of grind you use will affect the extraction rate of the coffee in your final beer.

The goal here again: balance. You want to find a grind setting that allows the best rate of extraction. If you over extract your coffee, you’ll get bitter, astringent flavors in the beer. And if you under extract, you won’t get enough of that coffee character.

“We try to do a coarse grind because we don’t want to over extract the coffee,” says Wade. “You want to get the best character you can out of it. You don’t want something that’s over extracted because that will be really bitter and astringent. But you don’t want something under extract either where you’re not getting that full richness of fruity and unique characters as well.”

The grind rate is so important to Wade that for a while he wanted his local roaster to use their top-notch equipment to grind the coffee, “so they could give us the nice coarse grind we were looking for,” he says. Nowadays, Wooden Robot has installed its own coffee bar in the taproom, investing in the machinery they needed to grind their coffee in house.

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso | Hop Culture

Chan and Cronin both caution though that with a coarse grind the extraction rate will be pretty fast. So you need to pay attention to the beer once you add the grounds to it. “If someone adds ground coffee [the extraction rate] would be quick even at 30 degrees,” says Cronin. “It would be like a cold brew so in 18 hours or 25 hours it would be like a quick cold brew overnight.”

The best advice Chan can give is to just keep checking the batch. “There is no hard and fast rule,” he says. “You have to pay attention to what the coffee does. It’s ready when it’s ready so people should be trying their beer every eight-to-twelve hours.”

Brewing With Cold Brew Coffee vs. Coffee Beans

Which actually brings us nicely to the method of creating a liquid concentrate to add to fermentation as opposed to straight up ground coffee.

At Wooden Robot, Wade actually creates a beer cold brew concentrate. “We do a cold extraction and instead of adding water we actually extract it in beer overnight,” says Wade. “We’ll use a 1bbl hop vac to add ground coffee into that, purge everything with CO2 making sure we’re getting as little oxygen as possible. We’ll fill that with beer and put that in our walk in cooler and let that steep overnight…for 16 hours. We’ll let that sit overnight and then first thing in the morning we’re using CO2 to push that concentrate into the larger tank of beer.”

Wade has found that by essentially making a cold brew, they “get as much extraction as possible without over extracting, so you’re getting the character you want,” he says.

Chan agrees that, “cold brew gives a really good aroma,” but he cautions that your standard operating procedures (SOPs) with this method need to be really buttoned up. “The worry if you do cold brew is how well will those beans store? Microbes could grow in there day or night.”

If you’re working with a cold brew concentrate, purging everything with CO2 along the way, as Wade does, will be essential to avoid introducing any oxygen.

Using Coffee on the Hot Side vs the Cold Side

General rule of thumb says that you should not add coffee on the hot side. “No one boils coffee beans in water to make coffee,” says Wade. But if you bring the kettle temperature down to 170 or 190 degrees there could be an opportunity for experimentation. It’s something Wade has considered because that temperature range is good for extracting a ton of flavor from the coffee, but he hasn’t actually attempted anything yet.

If you do decide to experiment with adding coffee on the hot side, Wade says it’s really important to consider contact time. “When we do a pour over in our coffee beer we’re doing it at 200 degrees, so you’re extracting all the character you want from the coffee, but it only takes three-to-four minutes,” he notes. “I would caution anyone to think about how much contact time you want with hot temperature because…if you’re at 200 degrees for more than two-to-three minutes you’re going to look at over extracting the coffee.”

Moksa’s Cold Steeped Series Photography courtesy of @moksabrewing | Moksa Brewing Co.

Temperature matters. “The higher the temperature, the faster the flavors will extract,” notes Gallanosa. “But you also have to be concerned about pulling out unwanted bitterness if your temp is too high.”

A safer bet, the cold side addition of coffee also makes more sense for “getting fruitier richer flavors out of the coffee and not getting that bitterness,” says Wade.

What Is the Right Amount of Coffee to Add to Your Recipe?

“Just like if you’re talking about hoping rates…it depends on the beer,” says Wade.

The right amount of coffee to add to a recipe will vary whether you’re making a blonde ale, an IPA, a stout, or any style in between. “If we’re working on a massive imperial stout versus our coffee vanilla blonde ale there will be a huge amount of difference in the coffee character you want in each of those,” says Wade.

He says that in their uber-popular coffee vanilla blonde ale called Good Morning Vietnam they use about 1/6th pound of coffee per barrel of beer. “It’s a pretty subtle balanced coffee character in a low alcohol beer with not a ton of competing malt or hop character.”

Photography courtesy of Night Shift Brewing

However, he notes that amount is on the very low end. You could easily double that quantity. And you’ll need to at a minimum if you’re making a darker style like a porter or stout. Typically, about eight ounces (0.23kg) to a pound of coffee per five-gallon batch will work well. But you’ll have to experiment yourself to find the best dosing rate for the beer you’re trying to make.

“The biggest challenge is probably balance,” says Night Shift Co-Founder Michael Oxton in the Hop Culture article Everything You Need to Know About Coffee Beers. “Too much coffee, or if you let it sit for too long, you risk bitterness or astringency. Too little coffee or time, and you don’t get enough flavor.”

Again it all comes back to achieving balance.

What Is the Right Amount of Contact Time?

Photography courtesy of Hop Culture

Contact time really depends on whether you’re using whole, cracked, ground, or liquid coffee.

At AleSmith, Cronin says when they use whole or cracked beans, they add them to a mesh bag and drop that into the beer for a few days. With ground coffee, however, again the extraction rate happens very quickly, so the contact time should probably number in the hours.

Like we’ve mentioned before, it’s all about monitoring the batch, testing it every eight-to-twelve hours until you get your desired flavor.

Considering Hops and Malt in Your Coffee Beer

As you build your recipe around the coffee it’s important to consider what hops and malts to use and in what amounts.

Hops

You have two approaches with hops. Most commonly, hop rates are lowered with coffee beers to make sure that the coffee character shines. “For us, we want the coffee to shine in beer so we’re not trying to muddy it up with competing hop characters,” says Wade. “We use a little bit of hops for bitterness and then we let the coffee add that aroma in place of where we might put hops in the recipe.”

The approach would be to find coffee and hop varietals that complement each other. “There are ways to do that, but you might not get that clear expression of coffee if you’re using a lot of later hops or dry hopping,” says Wade.

Without a doubt, hoppier styles that use coffee are pretty tricky. Normally, when it comes to hops in a coffee beer you don’t want them to dominate.

Photography courtesy of Wooden Robot Brewery

Malt

Conversely, malts can really help a coffee beer pop.

AleSmith takes a similar approach to malt that Wooden Robot does with hops. Cronin says that since AleSmith’s imperial stout recipe includes a grain bill with four-to-eight percent roasted barley, they actually lower that grain bill in Speedway Stout to let the coffee roast shine.

“The coffee roast will pick up that less roasted barley,” says Cronin.

As a complementary character, malts that bring dark caramel or roasted flavor are great for darker styles.

A lighter coffee blonde ale like Wooden Robot’s Good Morning Vietnam uses a little bit of Munich and honey malt. According to Wade, the toastiness of the Munich helps back up the coffee and gives it something to play off while the honey malt plays off the vanilla that also goes into that beer.

“You get a little bit of that toasty and the toasty, roasty character of the coffee with those lighter citrusy, floral, and apricot notes that work really well together,” says Wade.

Two Pitfalls to Avoid When Making a Coffee Beer

Photography courtesy of @alesmithbrewing | AleSmith Brewing Company

From the pros, how to avoid a couple pitfalls.

Avoid Oxygenation, Purge Everything With CO2

Just like oxygen is an enemy of beer, it can be with coffee as well.

Often that oxygenation can lead to that weird green pepper flavor. Which is why at Wooden Robot “for us…trying to keep oxygen out of the process is easiest to do on a closed system extracting ground coffee directly into beer on the cold side,” says Wade.

Across the board keeping oxygen out is paramount.

“There is always the possibility of adding microbes in with any herb or spice beer,” says Cronin. “As we’re opening bags before [the coffee] goes to the next process it gets purged out.”

And you need to double down on purging with CO2 if you’re using a cold brew. “Cold brew is scary because cold wants to take oxygen out of the air,” says Cronin. “Give that keg, or whatever you make cold brew in, a good CO2 purge before putting it in the brite tank.”

Avoid Letting Grounds Get Into the Final Beer

Cronin says at AleSmith they think those fines, or really small grinds, can oxidize the beer in a different way.

He likens it to “making a brew on Friday, coming to the office on Monday, tasting it because you need a little hit, and finding that it’s gross,” he says. “It keeps oxidizing in the beer as if it were [a cup] on a desk over the weekend.”

Best to avoid getting those really fine grounds into the final beer.

The Best Piece of Advice When Making a Coffee Beer

Photography courtesy of Wooden Robot Brewery

Here it is: The best piece of advice when it comes to making a coffee beer

Do Your Research: Drink Lots of Coffee

“My advice would be if you want to learn how to make a good coffee beer do a little reading on how to make a good cup of coffee because if you can extract it into water you won’t have to do a ton different to take that experience and turn it into extracting into beer,” says Wade.

In other words, drink lots of cups of coffee and “stay caffeinated,” laughs Wade.

Brew Your Best Coffee Beer With Ollie

Ollie is brewery management software built by brewers, for brewers. From robust inventory management to automated reporting, Ollie is the ultimate tool to ensure your brewery business never misses a beat. Check out a free demo today and learn why breweries all over are making the hop to Ollie.