The evolution of the craft beer industry has been driven by fine-tuning processes according to a set of regulations and using better ingredients so that brewers understand precisely what will come from those products. Spontaneously fermented beers toss all the conventional rules of brewing into the garbage, more or less.

The concept dates back ages—most commonly with Belgian brewers in the Senne Valley using spontaneous fermentation to create the lambic and gueuze family of beers—but has picked up steam in the U.S.

“There’s so much history behind it. It’s so cool,” says Allagash Brewmaster Jason Perkins, who prefers brewing untreated gueuzes. “It’s just no other added influence other than spontaneous character. It’s the best display of this type of brewing.”

With spontaneous fermentation, brewers whip up wort and leave it chilling in an open koelschip (aka coolship) overnight to inoculate with the natural organisms floating around in the local environment.

You’re not pitching any house strain of yeast and regenerating it for future batches of beer. Each time you brew a spontaneously fermented beer, you use a unique strain captured from the current weather conditions and environment.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Because the fermentation process is wild and untamed and requires a bit more nuance, brewing with spontaneous fermentation brings up a host of different questions.

What’s a good grist to invite the best fermentation? How long is ideal to let the wort sit in the koelschip? What temperature should it be overnight for the koelschip? How long should the beers sit in barrels before packaging? Experts in spontaneously fermented beers at Primitive Beer and Allagash Brewing answered some of our top questions about this process.

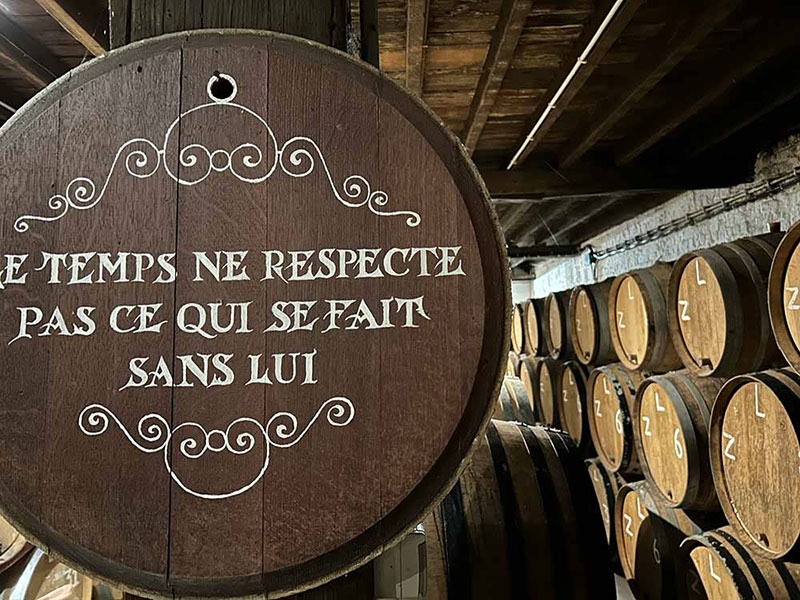

(Above photography courtesy of Allagash Brewing Company

What We’ll Cover in This Piece:

Affordable, Industry-Leading Brewery Software

What Are The Main Challenges of Spontaneous Fermentation?

Photography courtesy of Jester King Brewery

Perkins says one of the biggest challenges is accepting the amount of losses, so it’s essential to realize that going into the process.

“Losses are so much higher, specifically with evaporation over time in a barrel,” Perkins says. “But when you let go of as much control as you can, it’s better. One way you can is not using beer that doesn’t taste good.”

Perkins guesses that loss in spontaneously fermented beer is around fifty percent.

“It’s insane when you think about it,” he says.

One way around that could be blending, but that doesn’t always dilute off-flavors.

“Sometimes quality control is dumping [the bad-tasting beer],” he says. “Blending is wonderful, but what is unsaid is that part of blending is sending stuff down the drain. It’s absolutely real. You select barrels that work well together. The ones that don’t go down the drain.”

Perkins also notes that these types of beers are inherently connected to a time and place, and in a very process-driven beer industry, the top challenges skew from the norm.

“Temperature and weather patterns are important when making this,” Perkins says. “And this is a very difficult style to pilot. How you inoculate the wort depends on the building or koelschip.”

He adds, “You can’t throw wort in a parking lot. It’s not the same as a full-size koelschip. If you want to do true spontaneously fermented [beer], you have to go all in to mimic the traditional way of making a lambic-style beer.”

Primitive Beer Co-Founder Brandon Boldt echoes what Perkins said about going all in, explicitly stating that if you’re going to make spontaneously fermented beers, you really can’t scale down your recipe.

“It’s not about the flavor profile to me,” says Boldt, who only brews spontaneously fermented beers, leaning towards the lambic style specifically. “It’s about the magic, mysticism, and some of the culture behind making spontaneous fermentations of lambic-inspired beverages that way.”

Allagash makes so many different beers from their spontaneously fermented ones, so Perkins says one thing to consider is more intangible.

“We can control everything tightly with all other beers we make,” Perkins says. “You have to take off that technical brewer hat and throw on your artisanal brewer hat. You have to shift the way you think when you make [beers with spontaneous fermentation].”

What Is the Ideal Grist for Beers With Spontaneous Fermentation?

Photography courtesy of Primitive Beer

Boldt says to think about “protein, protein, protein” when putting together the grist for your spontaneously fermented beer.

“And as complex as possible,” he says.

Boldt says Primitive just follows lambic instructions for méthode traditionnelle.

“We’re not creative that way,” he says. “It’s roughly forty percent raw wheat, sixty percent malted barley. If you could have your barley be under-modified, even better. You’ll get everything you need out of it from a brewhouse standpoint.”

He says it might not be optimal, but that’s the more traditional way—especially when going through the multiple steps in turbid mashing.

“You can also achieve something similar from a single infusion at really high temperatures targeting alpha-amylase,” he says. “And using high amounts of adjuncts like wheat, oats, rye, and under-modified barley.”

Perkins says the Allagash spontaneously fermented beer is “super simple.”

“It’s forty percent unmalted white wheat (what we use in Allagash White) and sixty percent base malt, which includes pilsner and acidulated, and a little lactic acid.”

How Do You Mash-In for Spontaneous Fermentation?

Photography courtesy of Primitive Beer

Boldt starts with turbid mashing, a process where you put the mash through numerous temperature rests and remove starchy wort.

Turbid mashing is a way to achieve complex wort so the sugars aren’t decimated right off the bat and take time to develop.

Boldt elaborates on his method.

“I put the dough in at about 114 to 116 degrees Fahrenheit for a small first infusion where the liquor-to-grist ratio is low and is more like a damp grain,” he says. “I leave it in there for fifteen to twenty minutes, then add the next infusion of hot water at 200 degrees Fahrenheit to get us to a 126 degrees Fahrenheit rest.”

Boldt says they then remove about forty percent of that wort immediately after and send it to the kettle to boil and denature.

“Then we infuse hot liquor in the mash tun to get us to around 149 to 150 degrees Fahrenheit,” Boldt says. “And send another forty percent of that into the kettle to boil and denature.”

He adds, “We then get a high alpha-amylase rest at 162 degrees Fahrenheit and send about forty percent of that to the kettle and denature. Then all that turbid wort is sent back to the mash tun at 172 degrees Fahrenheit and then homogenized.”

From there, you clean the kettle and get it crystal clear, and vorlauf like you would normally. Boldt says he gives the wort a marathon boil for over four hours at that point before kicking it over to the koelschip.

What Are the Best Hops to Use for Spontaneous Fermentation?

Perkins explains that Allagash set out to make spontaneously fermented beers in 2007, aiming to respectfully honor the historic Belgian process in a different part of the world.

Traditionally, lambic beers feature aged hops along with spontaneous fermentation.

“We use aged whole-leaf Hallertauer Mittelfruh, bought in open-bin bales ahead of time by several years,” Perkins says. “We add it at about one pound per barrel to the kettle at the beginning of the boil.”

Perkins says the hops are very low in moisture, so it doesn’t scale. The measured alpha is zero.

“It’s about keeping stuff you want in check,” he says. “Keeping the preservability qualities maintained.”

Boldt says among the several critical factors of achieving the best spontaneously fermented beer, the first and foremost is some method of controlling acid development.

“That’s why we used aged hops or hops at all in our process,” he says. “And that is [because of] the antiseptic properties in those hops that mitigate the most acid development as well as some of the less-desirable bacteria, but still allows some nice lactic acid development over time, and allows wild yeast to thrive.”

Boldt adds that Primitive follows the more modern interpretations of lambic beers where the hops are whole cone and aged for more than three years. He says that Primitive aims for low-alpha and more “noble-like” hops that age to zero alphas quicker, because of the lower oil content.

“We add in one-and-a-quarter to one-and-a-half pounds per barrel into the first wort for the entirety of the boil to drive off some volatiles,” he says. “Some of that cheesiness is what you’d want in lambic-inspired beers.”

He adds that it isn’t to say high-alpha hops wouldn’t work, but it’s merely not what they are aiming for at Primitive. Ultimately, being in Colorado, Boldt says the hops they can readily get that are great for purposeful aging are Cascade or Willamette.

What Do You Need to Make Your Koelschip Work?

Photography courtesy of Primitive Beer

Boldt says before launching Primitive, he had attempted spontaneously fermented beer from the two-barrel to ten-barrel range and “didn’t create anything that I liked.”

“It was all rougher around the edges,” he says. “We figured it had to do with a smaller koelschip geometry, and we were putting it into smaller barrels.”

These challenges led them to go to more of a traditional size koelschip akin to what conventional Belgian lambic brewers used and a minimum of a five hundred liter puncheon. The méthode traditionnelle does not specify the exact size that your koelschip must be or where it should be, just that it must be open-top, indoors in a room overnight, and have access to untreated air, typically near one or more windows, for eight to sixteen hours.

“We’ve had a lot of success with that,” he says.

Boldt says the cooling rate is paramount, citing the koelschip inoculation should take twelve to eighteen hours.

“If you look at some of the large lambic producers and look at their koelschip and scaled it down, it would look like a brownie pan,” he says. “But that would cool it down way too quickly at a smaller scale.”

Boldt adds, “The geometry has to change. So you have to find a compromise so that it’s cooling correctly but also a geometry allowing for enough surface area of inoculation compared to the depth.”

Boldt says, however, there are lots of ways to get that inoculation, but the best advice he provides is to know your equipment.

“Once you figure out what you’re looking for, then you can know what your control points are,” he says.

What Are the Ideal Temperatures for Spontaneous Fermentation?

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

Perkins says in Portland, Maine, they can make beers with spontaneous fermentation only during November and December, depending on the overnight low temperatures.

“We look for an overnight low of twenty-five to forty degrees Fahrenheit,” Perkins says. “It took us years to discover this. You don’t get a sense of how these beers will be for about a year, so it took us years to figure out the overnight low temperatures.”

With that overnight low, Perkins says it stays there for about sixteen hours—give or take an hour or so based on temperature.

“The goal is to get to around sixty-five degrees Fahrenheit,” Perkins says. “From there, the wort goes to a stainless steel mixing tank to make sure the inoculation isn’t concentrated in any area before going directly into the barrels.”

Boldt says once they get the wort into the koelschip, he opens up all the windows and doors. He didn’t specify a range as Perkins did but said there is a minimum threshold to reach for the best spontaneous fermentation.

The overnight temperature has to be below forty-seven degrees Fahrenheit,” he says.

What’s the Turnaround Time for Spontaneously Fermented Beer?

After the koelschip, the next step is sending the spontaneously fermented beer into a barrel. But what’s a reasonable amount of time?

For Boldt, there’s so much to factor into the timeframe to package a beer with spontaneous fermentation.

“It depends on the desired beer and spontaneous process used,” he explains. “Generally, the quickest turnaround time is about eight months, and that is typically younger spontaneous beer served tranquil or perhaps table spontaneous beer like Meerts with effervescence.”

He notes that more often than not, people are drinking a gueuze-inspired three-year blend of spontaneous beer that spent at least an additional six months in the bottle before consumption and potentially a lot of cellaring.

“In this latter case, the beer is typically twenty-four months old before enjoyment, if not much older,” Boldt says. “In terms of barrels, our aging program typically doesn’t make use of a barrel for at least one year to as much as six to seven years, although most often used by two to three years.”

Perkins says Allagash’s beers are in French oak barrels for fermentation for a minimum of a year and a maximum of three years.

“I don’t even taste them before a year. It’s not all that pleasant before a year,” he says. “We’ve held them as long as four years—maybe if the beer is not quite as rounded, so we give it one more year. It depends on the character we’re getting.”

Two Great Examples of Spontaneously Fermented Beer

Perkins confidently says Coolship Resurgam, named after Portland, Maine’s motto, meaning “I shall rise again.” The gueuze style is 6.3% ABV and blends old and young spontaneously fermented beers.

“They are different every year because it’s part of the process. We accept it’s different every year,” he says.

Boldt says he is generally most stoked by Primitive’s unfruited beer, an unobscured showcase of terroir (the interaction of malted barley, raw wheat, aged hops, local water, airborne microbes, and time).

He points to Effectively Seasoned as the version he is most proud of. The gueuze-style spontaneously fermented beer is 6% ABV and is a six-year blend that includes a representative Puncheon from each brewing season at the time of bottling, with an average age of forty-two months into the bottle with an additional year of conditioning.

“I don’t know [if] I’ll ever have that opportunity again, and I’m proud of a beer that showcased the evolution of our beers since starting our blendery,” Boldt says.